China’s rise to economic and political pre-eminence could pose a challenge to developed market liberal democracies, argues Shamik Dhar, chief economist at BNY Mellon Investment Management.

When it comes to China’s long march to superpower status, Shamik Dhar likes to quote Zhou Enlai. In a 1972 interview, the then Chinese premier was asked about the impact of 1789’s French Revolution. “Too early to say,” he replied.

For Dhar, chief economist with BNY Mellon Investment Management, the quote, apocryphal though it may be, says everything about China’s mindset in its transformation from emerging market status. “It’s easy to forget the multi-millennia of history underpinning China’s claim to great nation status,” he says. “In the West, we’re used to a set of assumptions dating back to the Enlightenment and carried through the Pax Britannica or, more recently, the Pax Americana1. The message from China is different: those 250 years – which encompassed the French Revolution and witnessed the birth and triumph of Western liberal democracies – are really just a blip. Many of those ideas and assumptions we take for granted are up for grabs as China reasserts its ‘natural’ economic and political pre-eminence on the world stage.”

But it’s not just China. Dhar notes how the coming decades will likely see a wholesale reshuffling of the current order as countries at the top of the economic pack fall behind their emerging market counterparts. In just 11 years from now, according to one set of estimates, the US will have dropped from being the world’s first to third largest economy2. In its place China will take top slot followed by India. Likewise, Indonesia, Brazil, and Egypt couldleapfrog =some more developed markets with only Japan and Germany, of the current incumbents, still holding on to a place in the top ten. The same estimates suggest Asia’s GDP could account for around 35% of the global total by 2030, up from 28% in 2018 and 20% in 2010.

EMs in numbers: Leaving the West behind

- By 2050, Africa is expected to be home to 2.6 bn people, while India is billed to become the world’s most populous country by 2025. In contrast, the rapidly greying populations in the developed world, particularly in Europe and Japan, will act as a brake on economic growth. Source: Population Reference Bureau: ‘2018 World Population Data Sheet’, 24 August 2018)

- Today, eight out of 10 of the world’s busiest international flight routes are in the Asia Pacific region. Source: OAG.com (the Official Airline Guide), 12 April 2019

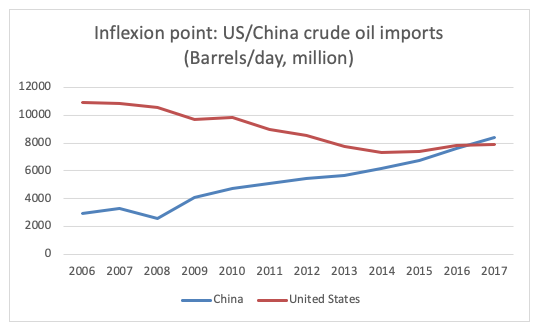

- In 2017 China overtook the US as the largest importer of crude oil. (Source: CEIC Data, OPEC, accessed 2 May 2019)

- In 2016, nine of the world’s 20 busiest shipping container ports were located in China. Fifteen of the top-20 were located in the Asia Pacific region. (Source: World Shipping Council, annual volume by 20-foot equivalent units (TEUs). Accessed 2 May 2019.)

Part of this is due to demographics – but look beyond the forecasts of population growth and the facts on the ground suggest the Asian century is already underway. In 2005, for instance, only three of the world’s ten busiest deep water ports were in China. Just a decade later, seven of the top ten were located there – with nine of the total in the Asia Pacific region. 3

The same holds true of air travel and air freight. Says Dhar: “People of a certain age might recall how Heathrow, Charles De Galle or JFK were once marketed as the world’s busiest airports. This no longer holds true. Today, if you’re looking for a list of the world’s busiest airports you wouldn’t look to Europe or the US: they’re almost entirely in Asia.”

In the corporate sphere too recent changes are hard to ignore. Each year, Fortune’s Global 500 report ranks the world’s largest companies by revenue. In 2008, US and European names dominated the list with only three Chinese companies in the top 100. A decade later and that dominance has retreated, with the number of European companies in the top-100 falling from 51 to 25 and the number of Chinese names rising from three to 21.4

For Dhar, the implications of this change are momentous – and he points to a wholesale repositioning in the locus of global production and consumption, not least in the commodities space, as one likely consequence.

“Consider the question of energy production,” he says. “In 2017 China supplanted the US as the world’s largest importer of crude oil. Yes, the growth in the shale industry, which made the US less reliant on imports, has had an impact – but it still points to a reshuffling of the deck and an upending the established order.”

As with commodities, so with goods and services. Dhar notes how over the past three decades the growth of developing countries and their emergence as the workshops of the world have lifted hundreds of millions of people out of poverty. But, as we move on to the next stage of global growth, that paradigm – of emerging markets being the factories and developed markets being the consumers – will likely fall away. “Instead, I think we’ll move to a position where a country like China is factory and consumer and services provider to the world,” he says. “That’s a very different proposition, not just economically but politically too.”

Source: CEIC Data, OPEC, accessed 2 May 2019

Unsettling implications

It’s here, in the realm of geopolitics, that Dhar believes the most profound and unsettling consequences of China’s emergence are likely to be felt. He highlights how the approach since the days of Kissinger and Nixon has been to bring China into the international fold, using the economic architecture created immediately after the Second World War. But that strategy has largely failed, he says, not least because China has managed to sidestep the spirit if not the law of the World Trade Organisation. But he believes the legacy of the Global Financial Crisis (GFC) has also played a part.

“Fifty years from now, the collapse of Lehman Brothers will be seen as one of the seminal events of this century,” he says. “Before the GFC, that post-Second World War economic and political settlement was secure. The US was the world’s dominant economic force: it was able to set the rules and, by and large, had the trust of populations in the West to do so.”

In a post-GFC world the mood music has changed and this in turn has emboldened China in its view that the classic Western liberal model is not the only game in town. “Right now, the West is having a collective crisis of confidence” says Dhar. “The US is aware of that – and it goes some way to explain the current efforts to renegotiate longstanding conventions in trade.”

For the future, investors might question whether China’s rise will be at the expense of other leading nations and if this can happen without conflict. Here, again, Dhar adopts a long-term view.

“From a historical perspective I’d argue it’s impossible for economic relations between countries to change as dramatically as they have done between China and the US without some kind of reset in the political relationship too. But I also suspect those ‘liberal norms’ – which form the foundations of Western democracies – are still the best way to meet people’s aspirations, regardless of where they live. If we are talking about lessons from history that seems to be a crucial one: time and again, rising economic prosperity has sparked demand for greater freedoms, including religious freedom, freedom of assembly and freedom of expression. In that sense, for all its claims to historical gravitas, I suspect China may still be in the early stages of a much longer journey.”

KEY POINTS

- China looks poised to become the world’s largest economy.

- An economic reset between China and the US could prompt a major shift in political relations.

- The global financial crisis has placed a real strain on the post-Second World War economic and political settlement

For Professional Clients only. This is a financial promotion and is not investment advice. Any views and opinions are those of the investment manager, unless otherwise noted. This is not investment research or a research recommendation for regulatory purposes.

For further information, visit the BNY Mellon Investment Management website.

1 The Pax Britannica was the period of relative peace between the end of the Napoleonic Wars and the First World War facilitated by the Royal Navy’s dominance of global shipping lanes. Pax Americana refers to a similar period of relative peace following World War Two built on US military hegemony.

2 Business Insider: ‘The US could lose its crown as the world’s most powerful economy as soon as next year, and it’s unlikely to ever get it back’, 10 January 2019. (Calculations based on GDP output after adjusting for purchasing power parity)

3 Source: World Shipping Council, annual volume by 20-foot equivalent units (TEUs). Accessed 2 May 2019.

4Source: Fortune: ‘Global 500’, 19 July 2018