Is the imminent default of Chinese property developer Evergrande about to destabilise the wider economy? Or has the risk been overblown?

- The property developer has been downgraded by Fitch and Moody’s, with both rating agencies suggesting a default is likely

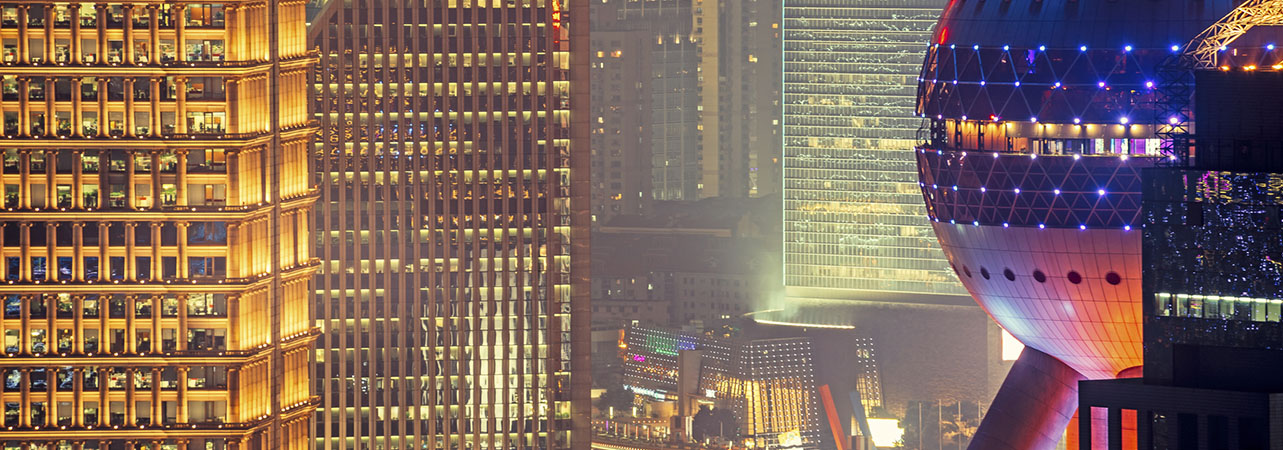

- Evergrande is a large and influential company, now owning more than 1,300 projects in over 280 cities

- China’s debt burden doesn’t look high by developed market standards, but is stretched by emerging market standards

There have been some dramatic statements made about the difficulties of Chinese property developer Evergrande: it is China’s ‘Lehman moment’ or it undermines the integrity of China’s entire financial system. There are those who believe it will bring China tumbling down like a house of cards. Is the fate of this, admittedly problematic, property developer really so important?

A number of elements are not in doubt. The first is that Evergrande is in trouble. The property developer has been downgraded by Fitch and Moody’s, with both rating agencies suggesting a default is likely. The company itself has said it is in dire need of additional financing and already came close to default in September 2020.

There is also little doubt that Evergrande is a large and influential company. It has expanded rapidly and now owns more than 1,300 projects in over 280 cities. At the end of June it had commitments to build a further 1.4 million properties. It is hugely indebted and, as such, vulnerable to any slowdown in China’s precarious property sector.

That China has a debt problem is also uncontroversial. While its debt burden doesn’t look high by developed market standards, it is stretched by emerging market standards. Emerging markets have an uncomfortable history with debt, which has often been the catalyst for a crisis. Equally, one well-connected company can be the straw that breaks the camel’s back of a country’s banking sector.

However, the Chinese authorities are well-aware of the problem and have the example of neighbouring Japan as an important example of what not to do. Japan let sliding property and land value undermine its banking sector for decades rather than taking action. China is unlikely to repeat that mistake and has already shown itself willing to make the necessary adjustments.

The government is likely to step in to restructure the debt and avoid contagion into the onshore property market. The bond market in the region appears to be unconcerned about wider contagion, with little movement in corporate bond spreads or government bond yields. The consensus appears to be that this is an idiosyncratic event, with limited risk of spillover.

It is instructive, however, how quick some economists have been to call the demise of the Chinese financial system. It seems that there are many who are waiting for China to fail.